*Institutional Repository

In November 2011 the CUNY Faculty Senate adopted a resolution supporting the development of an open-access institutional repository (IR). It was further resolved that the faculty — working through the University Faculty Senate and the Office of Library Services — should develop guidelines for depositing materials into that repository. CUNY Academic Works, the name given to the CUNY IR, was launched in March 2015. Representative of a range of scholarly and creative works by members of the CUNY community, the repository now contains over 9,150 papers, including peer-reviewed journal articles, conference proceedings, and student works such as theses and dissertations. With Academic Works off to a successful start, it is time to begin a conversation about what guidelines faculty wish to adopt relating to the archiving and sharing of their works in this new institutional repository.

Brief History of Open Access

The open access movement in the scholarly communications field grew out of the confluence of three issues: economics, ethics, and widespread access to the Internet. Economic concerns related to escalating prices for journals, particularly in the STEM disciplines, coupled with the fact that much of the research published in these journals was government funded, in effect, requiring taxpayers to pay twice, once for the research and then again for access to the research results. Increasingly frustrated by copyright agreements restricting their ability to broadly disseminate their works and by the fact that publishers, not authors, were the ones reaping the direct financial benefits, scholars were inspired by the World Wide Web to find new ways to reach a wider audience. While recognizing the added value of working with experienced publishers, increasingly authors are questioning whether it is necessary to give publishers complete copyright control over all their works. Some authors are opting to publish their work in open access journals; others are publishing in pay for access journals and then self-archiving a copy in an open access repository. (For a more complete, but focused history of the open access movement we recommend Peter Suber’s Open Access Overview).

Open Access Journals vs. Open Access Repositories

Open access (OA) literature has been defined as “digital, online, free of charge, and free of most copyright and licensing restrictions” (Suber, Overview). As journals move from print format to electronic dissemination, some, including mainstream journals, are now either completely or partially open access. Some appear to be using limited open access as a public relations tool: Springer recently opened up a small subset of its articles to mark National Criminal Justice Month. In addition, a growing number of journals that are not following an open access model are expressly permitting authors to self-archive some version of their published articles on web sites including their institutional repository (see SHERPA/RoMEO, a database of publishers’ policies on copyright and self-archiving). To make it easier to protect an author’s right to deposit works in an institutional repository, many faculty bodies are adopting policies requiring its members to do so, effectively overwriting any provisions in publisher agreements to the contrary. Luckily, these policies do not appear to have limited in any way the places in which authors are choosing to publish.

Today, Directory of Open Access Journals includes over 11,000 open access journals and Registry of Open Access Repositories lists over 4,000 open access repositories. CUNY is the publisher of some of these open access journals (see e.g., CiberLetra, Revista de Critica Litereraria y de Cultura, Journal of Literary Criticism and Culture, Journal of Interactive Technology and Pedagogy, LLJournal, and Urban Library Journal). Using the policies of the Urban Library Journal as an example, it is not unusual for open access journals to unabashedly encourage authors to deposit their works in institutional repositories so long as there is an acknowledgement of its initial publication in said journal.

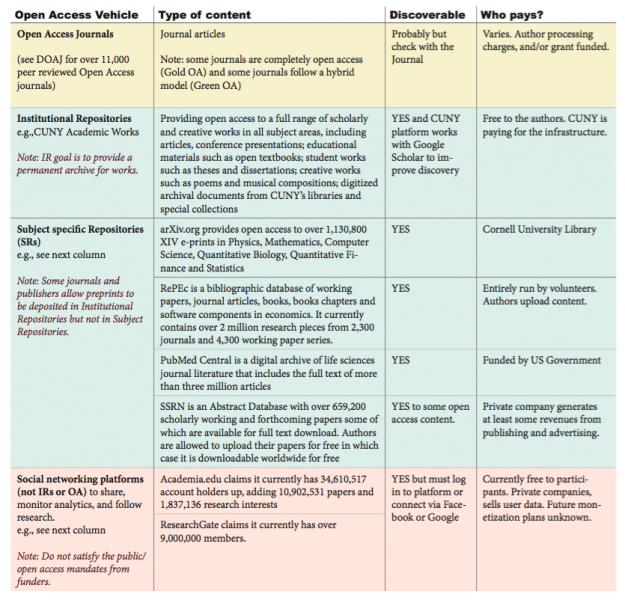

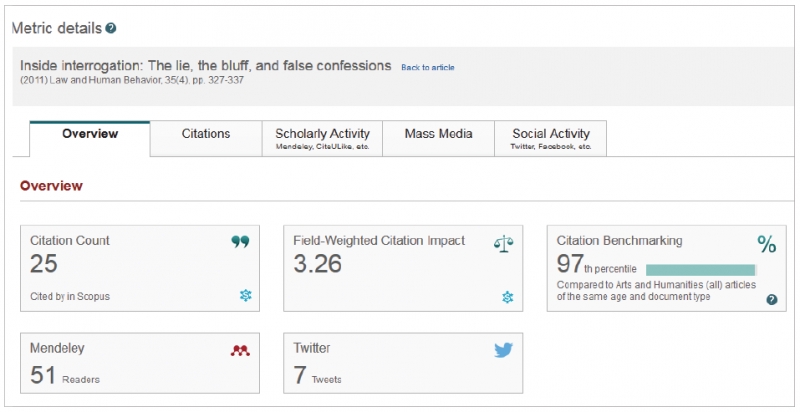

Some repositories are established and maintained by academic institutions like CUNY’s Academic Works; some are focused on data and others serve the interests of a specific discipline. Increasingly popular are the social networking platforms created by for-profit companies that enable researchers to share their work, promote their research interests and communicate with one another. These platforms are neither repositories nor open access vehicles. Key features of open access repositories are the permanence of the posted content and the unimpeded access for all viewers. The social media platforms allow account holders to remove their materials after posting and force potential viewers to create accounts before gaining access to the work. There is considerable debate about the appropriateness of these networks for sharing academic work, the long-term goals of the companies behind them, and the ethical ramifications of using them. Nevertheless, they have wide appeal and do demonstrate the principle underlying the open access movement: the desire to widely share one’s work. The chart shows some of the tools John Jay faculty are using to provide access to their works.

Policies to deposit work in Institutional Repositories

As illustrated by activity of John Jay faculty, CUNY’s commitment to open access is still in the early stages. Does CUNY, a public university funded by taxpayers and a community of scholars interested in sharing its research with the broadest possible audience, want to increase that commitment? Faculty at the University of California, Harvard, Kansas State, Rutgers and MIT and over 530 university or research institutions have adopted policies requiring faculty to deposit their articles in their respective institutional repositories, as reported in The Registry of Open Access Repository Mandates and Policies (ROARmap). Might departments and/or colleges and/or the entire City University be ready for that step? What information does the faculty need to make this decision?

Download this chart as a PDF (with OCR)

—

Learn more and join the conversation

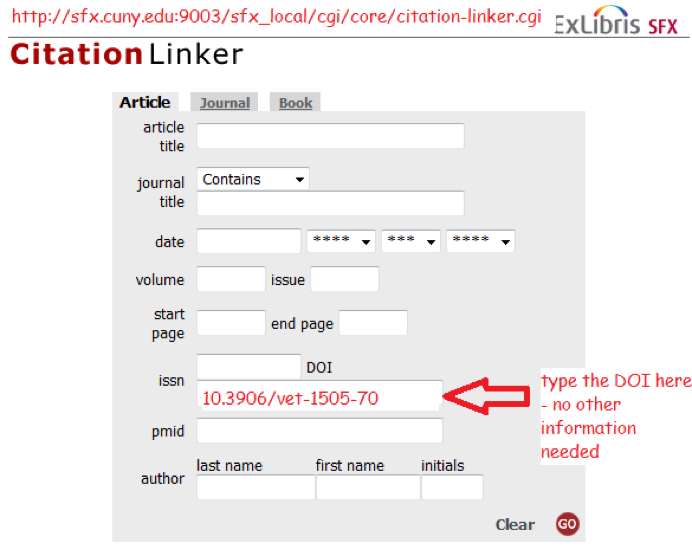

For more information on CUNY Academic Works and how you can join the conversation and/or add your works to the CUNY IR, take a look at the guide at guides.lib.jjay.cuny.edu/AcademicWorks.

For a focused history of the open access movement we recommend Peter Suber’s Open Access Overview at legacy.earlham.edu/~peters/fos/overview.htm.

For details about publishers’ policies on copyright and self-archiving, please consult the SHERPA/RoMEO database at www.sherpa.ac.uk/romeo.

Directory of Open Access Journals can be accessed at doaj.org.

Registry of Open Access Repositories can be found at roar.eprints.org.

You may review the Registry of Open Access Repository Mandates and Policies (ROARmap) at roarmap.eprints.org.

Jeffrey Kroessler, Maureen Richards and Ellen Sexton

—

More from the Spring 2016 newsletter »

As team-based learning becomes more prevalent in undergraduate education, students need space to work on group projects. The Lloyd Sealy Library still provides quiet space for individual work, but our four

As team-based learning becomes more prevalent in undergraduate education, students need space to work on group projects. The Lloyd Sealy Library still provides quiet space for individual work, but our four